A Woman's Place

Exploring a Woman's Role in Politics, Education, and Society Through History and Personal Experience

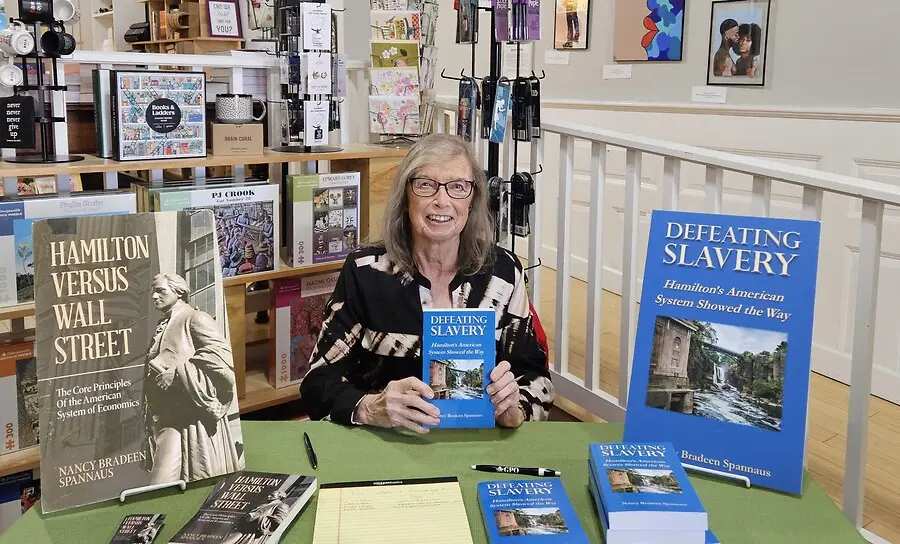

Editorial Note: The following article was written in January of 2018, as part of an essay contest for the Daughters of the American Revolution, but I think it’s most relevant for a site devoted to women’s roles in society. Since that time, I’ve written three books, one of which has done very well for a self-published volume (Hamilton Versus Wall Street). I’ve also contracted a new cancer which makes my future uncertain. But, I persist, and encourage others to do as well.

During my first campaign for public office in 1989, a woman friend gave me a tee shirt which provoked the title of this essay. “A Woman’s Place is in the House…,” it began, immediately followed by “and in the Senate.” As I was running for a seat in the U.S. Senate at the time, the gag was totally appropriate, and it regularly provoked laughter among those who saw me wear it.

But, of course, there is a more serious question embedded in this joke. What actually is a “woman’s place,” not only in the world of politics, but also in society as a whole? Is there even a particular “woman’s place” at all? And, more germane to this essay, how was I equipped to deal with and answer this question?

I have to tell you straight out that I am not your traditional modern feminist. I am not and have not been a campaigner for abortion rights, or the Equal Rights Amendment, or for eliminating gender distinctions in matters of the family. I am happily married to my husband of nearly 50 years, raised two young men, and have been the chief cook and household manager most of that time, without resentment. I like to dress up “purty” and receive compliments on how I look—especially when people say I don’t appear as old as my 74 years.

But at the same time, I clearly view a “woman’s place” much differently than did my homemaker mother, and many other women today. I have not only run for political office six times, but also been the chief editor of a national newspaper and a national newsweekly magazine, a widely published author on current affairs as well as early American history, and a leader of an international political association. What prepared me to do that? And what does my experience and thought contribute to answering the question of a “woman’s place?”

A Little History

I grew up in a family steeped in New England traditions—devotion to education, frugality, and, in our case, careful avoidance of personal disclosure. On my mother’s side, which had considerable influence on me, it was also decidedly a matriarchy.

A brief explanation. Significant men in the generation of my mother’s parents were simply not there. My grandfather had abandoned his family when my mother was under 5 years old, leaving his wife, my mother’s mother, with the job of raising three young children (and one older one) alone. She had gone to work at night, writing the society column for the Portland News-Herald—the only woman on the newspaper staff. My mother’s sister’s husband had died young, leaving my aunt to fend for herself. She eventually became executive secretary to a shoe industry executive, and was universally seen as a very strong woman.

The word among these two women, with whom I spent several summers in my youth, and my mother as well, was that “you can’t trust a man.” They pointed to a family history of male miscreants, and prided themselves on being able to manage without. Their focus was limited to the family.

My father represented a clear countervailing, and broadening influence. As a Classics professor and twice a fellow at the Princeton Institute for Advanced Studies, he was rigorous scholar and very demanding of me, his oldest child. He had an in-depth historical view (“Everything after the 5th Century B.C. was current events,” he said.) He never gave any indication that my gender should interfere with the highest level of intellectual achievement—and pushed me to go to a top woman’s college, Bryn Mawr, in order to get the best education possible. Bryn Mawr had a strong Classics tradition, including school songs in Classical Greek and a de facto patron goddess, Athena, the Greek goddess of wisdom (and war). I majored in philosophy.

A Noble Philosophical Tradition

Ancient Greece is a fruitful place to start in looking at the potential role of women in society. In addition to the role of Athena as the goddess of wisdom, we have the views of Plato and Socrates. There is one particular section of Plato’s Republic which is worthy of note. In Book VII, Plato writes about the stages of life:

…And when they have reached fifty years of age, then let those who still survive and have distinguished themselves in every action of their lives and in every branch of knowledge, come at last to their consummation; the time has now arrived at which they must raise the eye of the soul to the universal light which lightens all things, and behold the absolute good; for that is the pattern according to which they are to order the State and the lives of individuals, and the remainder of their own lives also; making philosophy their chief pursuit, but, when their turn coms, toiling also at politics and ruling for the public good, not as though they were performing some heroic action, but simply as a matter of duty…

…You must not suppose that what I have been saying applies to men only and not to women…. (emphasis added)

I wrote my senior thesis on Plato, and implicitly embraced this idea heartily then, and kept it in mind in my subsequent endeavors. I encountered other great philosophers, also in the Platonic tradition, whose actions showed they shared Plato’s view on the lack of limits for women. Among the most notable was Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, the great philosopher/scientist of Germany in the 17th Century. Leibniz’s most devoted pupils were three German princesses, the Electress Sophia, her daughter Princess Sophia Charlotte, and Princess Caroline of Anbach. They were the beneficiaries of not only his mathematical and scientific genius, but also his thinking on statecraft, which involved the promotion of institutions of learning and fostering of the public good.

Meanwhile, in England, Leibniz’s supporters were close collaborators of Queen Anne, who played a significant role in promoting the colonization of America, and spreading the same philosophy of statecraft on this continent.

One looks pretty much in vain to find prominent women in the American Revolution, but the lack of visible heroines does not mean that they didn’t exist. On my recent trip to the Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia, I discovered that there was a Daughters of Liberty organization that worked parallel to the Sons of Liberty. Many credit them with organizing the boycotts of British goods during the rebellions against the Stamp Act and the Intolerable Acts. They reportedly melted metal into bullets. These women provided their time and talents far beyond their immediate families and communities, to not only serve the public good, but make a revolution.

My own concentration of study on the American Revolution, which began in the mid-1970s, did not focus on the role of women, but on the ideas which the leading Founders, such as Benjamin Franklin and Alexander Hamilton, developed in order to create the new nation. And while these heroes of mine were by no means concentrated on advancing the role of women per se, their political ideas were equally applicable to liberating the minds of men and women.

Making History

For as long as I can remember, I always I felt an obligation to act to improve society. By the time I finished my formal education, this concept had broadened considerably beyond just working in a local community, to encompassing the world as a whole. When I had my children in the early 1970s, my determination to play that larger role in the world, specifically through politics, became even stronger. I owed it to my children, as well as those of others, to create a world where they could thrive. My husband shared this view.

Thus, I joined a political association. In 1973, I became editor-in-chief of its weekly national newspaper. This involved working with many men and women who were writers and researchers, as effectively as their “boss.” At the same time, I took on responsibility within the leadership body of my political association, both for guidance of political campaigns, and of the intellectual work required to buttress those campaigns. My particular area of concentration was the American Revolution, an area which ultimately resulted in the publication of the book The Political Economy of the American Revolution (with a colleague), and an expansive series of studies of the deeper roots of American revolutionary thought in the ideas of the Italian Renaissance.

By the early 1980s, I became a national spokesperson for the American System of political economy, and then the head of an organization called the Club of Life, which promoted pro-life policies in the broadest sense—from economics to anti-war to health. This latter role led me to be engaged in international politics, including United Nations events.

In the late 1980s, circumstances led me to expand my role once again. My husband was sent to prison in a political prosecution, and I felt I had to take a more aggressive role in the public arena than being primarily an editor. So, I decided to run for political office, championing those same American System policies which I had studied, and fighting the political injustice which had led to the incarceration of my husband and others in our political movement.

1989 was a year of Revolution (the fall of the Berlin Wall), but it was not yet an era of many female national candidates. Yet, in my campaigns for U.S. Senate, Governor of Virginia, and U.S. Congress, I did not find my gender to be a major factor in the way I was treated. Political prejudice, yes; that was quite enough.

Obviously, I didn’t win any of my political campaigns. My greatest vote total was against Sen. John Warner in 1990, because the Democratic Party refused to run a candidate; that was nearly 200,000 votes. My most visible impact came in 1994, when I headed a non-partisan political action committee to defeat Oliver North for U.S. Senate, which even garnered some international media attention. Meanwhile, I used my campaigns both to educate citizens on the American System economics, and to redress injustices, including pending executions of men who protested their innocence. Happily, two of those men have eventually been freed from prison.

In 2002 I returned to my editorial role, which I fulfilled until 2015.

I have retired, but will actually never really retire. It is still my obligation to use what knowledge I have acquired to educate, and if possible, inspire, my fellow human beings to improve this world—indeed, to bring it out of crisis. My activities, including starting a blog and joining DAR, have been embarked on with this intent. That is my role as a privileged human being—and thus as a woman as well.