The Happiness Paradox

High Motivation Meets Operational Friction: The Hidden Cost of Unclear Processes

Introduction

Stress often carries an unfair reputation as a personal failing—a lack of resilience or an inability to "hack it." However, organizational behavior theory suggests the environment, not the individual, is often the architect of burnout. Rice (2019) defined stress not as a weakness but as a condition where environmental demands exceed an individual's ability to cope, leading to potential psychological or physiological damage. To investigate these environmental architects, a survey gathered data from 23 professionals across a diverse social media network. While many participants work in education, the sample represents a broader slice of the modern workforce. The instrument, a 10-question Likert-scale survey, measured three core dimensions: general feelings about work (climate), job attitudes (motivation), and organizational support for well-being.

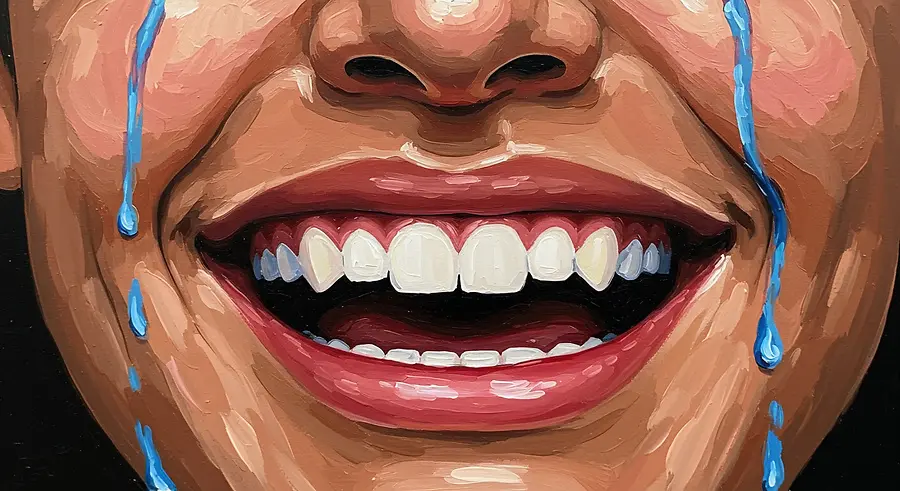

The data tells a story of a "Happiness Paradox." The respondents are not disengaged, quiet quitters; they are highly motivated, proud professionals who love why they work but are increasingly exhausted by how the work is managed.

The Good News: Pride and Resilience

To interpret the survey data, weighted averages were categorized into three distinct levels: scores between 1.0 and 2.5 were considered low, scores between 2.5 and 3.5 were moderate, and scores above 3.5 were considered high.

At first glance, the landscape looks thriving. The participating professionals generally view their work environments positively, with all three section averages falling comfortably into the high category:

- Section I (General Feelings/Climate): 3.81 (High)

- Section II (Job Attitudes/Motivation): 3.85 (High)

- Section III (Well-being/Stress): 3.59 (High)

What drives this high morale? The data points to a deep well of organizational pride. The highest-scoring item on the entire survey was Question 6, which asked respondents whether they were proud to tell others about their organization. This question received an average score of 4.17, with no respondents selecting the lowest option. Farrell (2018) noted that organizational culture comprises the values and behaviors that drive a mission. The high pride scores suggest that these professionals find the mission resonant. They know who they are, and they believe in what they do.

This resilience is visible in the distribution of individual averages (see Figure 1). The data skews overwhelmingly positive, with 17 out of 23 participants maintaining an overall average in the high range.

Figure 1

Frequency of Composite Scores Across Low, Moderate, and High Categories

Note. N = 23. The chart illustrates the distribution of weighted average scores for all respondents. Categories are defined by the following mean score ranges: Low (1.0–2.5), Moderate (>2.5–3.5), and High (>3.5–5.0).

The Hidden Friction: When Process Kills Purpose

Despite the high morale, a silent friction is wearing down the workforce. Question 10 asked participants if "the way things are done" in their organization adds to daily stress. Suddenly, the unity seen in the "Pride" scores fractures (see Figure 2).

Figure 2

Employee Responses Regarding Operational Stress

Note. N = 23. The figure displays the frequency of raw responses to the survey statement, "The way we do things in my organization adds to my daily stress." Scale ranges from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree). For the composite analysis in Figure 1, these scores were reverse-coded so that higher values represented positive well-being.

As shown in Figure 2, responses were sharply polarized. More than half of the respondents (52%) agreed that their organization's processes add to their daily stress. This frustration appears inextricably linked to a lack of clarity. While pride is high (4.17), the survey item regarding whether "Leadership's decisions and communications are fair and transparent" received only a moderate average of 3.13.

This contrast paints a vivid picture of the modern employee experience: Professionals love the mission but struggle with the mechanics. They are motivated by the work's purpose but stressed by the workflow's ambiguity. Notably, this stress does not stem from a lack of safety nets. Nineteen out of 23 participants (82%) indicated they knew precisely how to access support resources. Even the respondent with the lowest composite score (a 1.6) reported high awareness of these resources. The safety net is visible to everyone, yet the logistical hurdles of the workday remain a shared burden that no amount of "resilience" can fix.

Best Practices: Clearing the Track

To bridge the gap between high motivation and moderate process satisfaction, leaders must stop asking employees to "force it" and start removing the hurdles.

1. Adopt a "Document Everything" Protocol

The data suggest that the "moving target" of unclear expectations is a primary stressor. To fix this, organizations can adopt a "Document Everything" culture. This Universal Design strategy requires that all verbal requests or meeting assignments be followed up with a written summary including clear instructions, due dates, and priority levels. By making the "what" and "when" crystal clear, leaders reduce the cognitive load employees spend deciphering expectations. This simple shift removes the ambiguity that fuels process stress and ensures communication is transparent—addressing the moderate scores in Question 9.

2. Audit Operational Friction

Since over half of the respondents linked stress to organizational processes, leaders should examine which specific workflows generate friction. Demissie and Egziabher (2022) emphasized that organizational culture influences institutional effectiveness. A culture that prioritizes rigid hierarchy over agility may inadvertently create cumbersome procedures. Leaders might conduct focus groups to identify administrative tasks that consume disproportionate energy—the "death by a thousand cuts" tasks—and work to streamline or automate them.

3. Normalize Support Utilization

The data shows that employees know where to find help; the challenge lies in normalizing access to it. Guo and Zhu (2022) suggested that organizational compassion involves collectively noticing and responding to pain within a system. Leaders can move beyond simply listing Employee Assistance Programs (EAPs) in a handbook by modeling their use. Openly discussing mental health maintenance can destigmatize the utilization of these resources, encouraging staff to seek support before stress becomes chronic.

Conclusion

The survey findings offer a hopeful but urgent perspective on the workforce. The data indicate that organizations possess the most difficult-to-build asset: a workforce with deep pride and high motivation. However, operational processes and communication gaps are acting as "unnecessary hurdles," tripping up the most dedicated runners. By implementing clear protocols—like "Document Everything"—and aligning daily operations with the stated mission, organizations can finally clear the track, allowing their people to run freely toward the purpose they already believe in.

References

- Demissie, D., & Egziabher, F. G. (2022). An investigation of organizational culture of higher education: The case of Hawassa University. Education Research International, 2022, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/1222779

- Farrell, M. (2018). Leadership reflections: Organizational culture. Journal of Library Administration, 58(8), 861–872. https://doi.org/10.1080/01930826.2018.1516949

- Guo, Y., & Zhu, Y. (2022). How does organizational compassion motivate employee innovative behavior: A cross-level mediation model. Psychological Reports, 125(6), 3162–3182. https://doi.org/10.1177/00332941211037598

- Rice University. (2019). Organizational behavior. OpenStax.