Hostile Architecture and the Failure of Urban Compassion

How Design Choices Shape Belonging, Vulnerability, and the Right to the City

Cities are never neutral. Every design decision—every bench, ledge, railing, and public square—signals who is welcome to stay and who is expected to move along. In recent years, many cities, including New York, have increasingly embraced hostile architecture: design strategies intended to prevent certain behaviors by making public space uncomfortable or unusable.

Benches divided by metal bars. Spikes on flat surfaces. Sloped ledges that repel sitting. These are not incidental details. They are deliberate interventions meant to control presence.

Such measures are often justified in the language of safety, cleanliness, or efficiency. In practice, however, they displace vulnerability rather than address it. Hostile architecture does not solve homelessness—it renders it invisible, quietly reshaping cities into places that are less humane for everyone.

Nowhere is this contradiction more evident than in New York City.

By 2025, New York has reached one of the most severe housing insecurity crises in its history. On any given night, thousands of people live unsheltered, while more than 100,000 sleep in shelters across the city. What is often overlooked is who these individuals are. Roughly two-thirds of New York’s sheltered homeless population are families, not single adults. Homelessness in New York is not marginal—it is widespread, increasingly affecting parents, children, and working households.

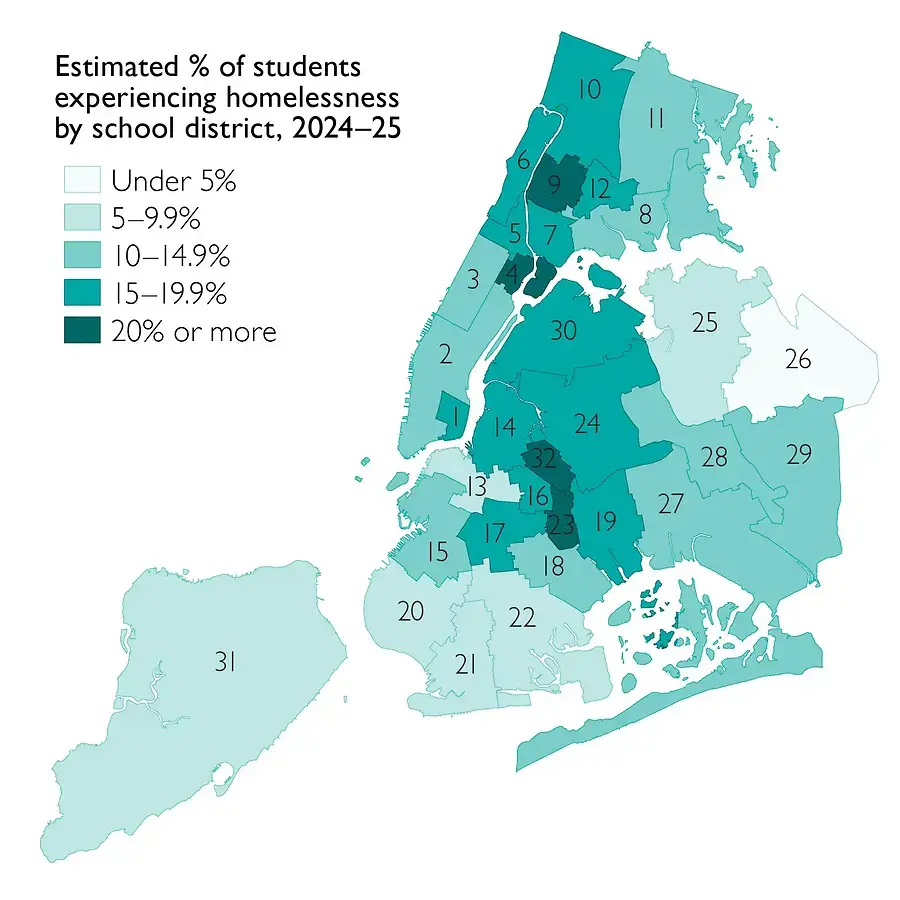

The scale of child homelessness is particularly striking. During the 2024–2025 school year, nearly 150,000 public school students—approximately one in seven—experienced homelessness. These are children attending class while living in shelters, temporary housing, or unstable arrangements. Any narrative that frames homelessness as an exception collapses under these numbers.

Mental health and substance use are also part of this reality, though they are frequently misrepresented. Among people living unsheltered in New York City, an estimated 24 percent experience serious mental illness, including conditions such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or severe depression. Many also struggle with substance use disorders. These figures matter not to stigmatize, but to highlight systemic failure. Mental illness and addiction are health conditions—not design problems—and they do not justify environments that punish people for existing in public space.

Hostile architecture treats vulnerability as a nuisance to be managed rather than a condition to be addressed. When cities install benches that prevent lying down—or remove flat surfaces entirely—they are not simply discouraging sleeping. They are denying rest. And rest is not a behavior. It is a human need.

This reveals the deepest flaw of hostile design: it is never selective. When cities prevent certain actions, they prevent them for everyone. A bench designed to stop someone from sleeping also prevents an elderly person from lying down, a pregnant woman from resting, a parent from sitting comfortably with a child, or a person with a disability from pausing without pain. Design that excludes the most vulnerable ultimately excludes the ordinary.

Public space thrives on flexibility. It is meant to absorb difference, slowness, unpredictability, and care. When those qualities are stripped away in the name of control, cities become tense rather than safe—empty rather than alive.

Inclusive urbanism offers a fundamentally different approach. It begins with a simple truth: homelessness is not an identity. It is a condition—and in today’s economic and social landscape, it is one almost anyone can experience. Job loss, illness, family separation, rising rents, migration, or climate-related displacement can push even stable households into crisis. The distance between being housed and unhoused is far smaller than many policies are willing to admit.

Inclusive design does not claim to solve homelessness on its own. But it refuses to make it worse. It recognizes that architecture carries responsibility—that public space should never be weaponized to compensate for failures in housing policy, healthcare, or social services.

Hostile architecture, by contrast, is fundamentally anti-urban. It replaces care with control and shifts responsibility away from institutions onto objects: a bench instead of housing policy, a spike instead of a support system. It prioritizes appearances over outcomes, comfort for some over dignity for all.

Cities that invest in exclusion ultimately design against themselves. Cities that design with compassion—recognizing vulnerability as a shared human condition—create public spaces that are safer, more resilient, and more alive.

Because a city that works for its most vulnerable residents is not weaker.

It is stronger.